THE START

I've always loved getting lost. Taking my thoughts for a walk without knowing what’s around the next corner. It makes me think and act differently – somehow more myself – returning home sweatier, maybe muddier, but always invigorated and more alive than when I left.

This compulsion to explore – to walk and climb, peer and prod, meet people, ask questions, and share stories – is at the heart of who I am and what I create. I’m looking for the corners that lift. Digging beneath the surface to scoop out the meaning inside. The human history, tragedy, comedy, folklore, and culture that define a place become the true landmarks in my work

We live in an age of curated certainty. Where devices reduce living landscapes to predictable routes and star destinations. To walk without guidance, to feel the surroundings, and to talk with those who call it home—these acts help me return wayfinding to what it's always been—a connection between people and place.

THE WALK

Some days are lost to local libraries and museums. Others are spent simply getting lost. Whole weeks of walking. Thousands of photos. Long, sprawling lists. Mentally and visually archiving each journey. Discovering a city at the top and bottom of its day, before the streets steam with sunshine and people, and late enough to see what’s left and who remains.

I don’t always walk alone. Local historians, tour guides, writers and architects all help flesh out the facts, myths and legends. But often, it's the spontaneous encounters with strangers that really stick – a snatched interaction during London rush-hour; a quiet conversation on a bench in the Shanghai suburbs; listening to a story in the doorway of a DC liquor store; leaning in to hear above the din of a busy Beijing hutong. Real human stories of lives held together by place.

Often, the story has no narrator: it's simply there. In the soaped-up shop windows of a failing shopping mall. An abandoned pram on a sea of broken bricks. A marriage proposal with a ring delivered by drone. A man asleep in a car, his head resting on a blaring horn.

Walking and drawing help me understand the world and my place within it.

THE STUDIO

I work in pen and ink on archival cotton board. I always draw standing up. I consult the lists, photos and notes compiled when walking, alongside digital maps, piles of books and the internet. Friends tell me it’s a sort of maverick obsession but the truth probably lies in incredibly comfortable shoes.

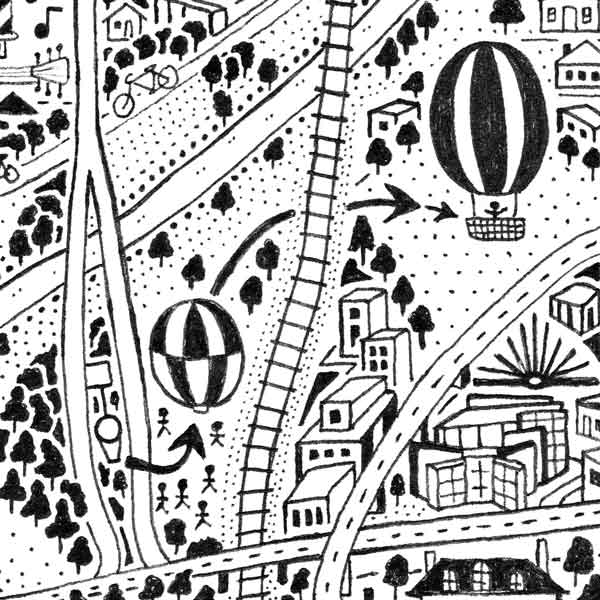

The natural features and topography are drafted first – the mountains, coastlines and rivers that give a place its face. The human-made environment and culture always follows. Capturing a place on canvas is a tapestry of problems to solve. Building layer upon layer of cultural references, personal experiences, visual puns and imagined futures. Listening to music, local news and deep-dive podcasts help me tune in when miles away.

THE ART

I’m exploring the landscape and environment as a place of memory, imagination, and belonging, mapping an emotional terrain. In my work, the streets, buildings, and landmarks serve as vessels for meaning – narrating the psychology and social spirit of the place. It’s a process that looks to art instead of words to carve out the truth of slow journalism with the scope and storytelling of great literature.

My practice is compared to psychogeography but, while there are similarities, I'm purposefully wandering: documenting a collective knowledge of the lived experience. I feel more kinship with the phenomenology of place – an investigation into the identity of places and our deep attachment to them.

I think of my art as portraits of place. Maps of the mind. Love letters to certain landscapes – buzzing with hidden details, meaning, and narrative, equally serious and playful. A collage of fact and fiction, human patterns, systems, technologies, iconography, and architecture that captures society in all its states of progress, decline, romance, and glory.

Walking and drawing help me understand the world and my place within it. I hope my art, a mere snapshot in time, is meaningful for anyone who connects with the places and subjects I explore.